“How can poverty in India be fixed? Can the government just give money to all the poor people?”

These were the concerned questions I got last week after I gave a talk based on my article “Misconceptions About Income Distribution in India.”

I don’t have a good answer to the first question, but the second question led to an interesting discussion around Universal Basic Income (UBI). The idea is simple: the government gives a fixed income to everyone in the country, and the handout gets rid of most of the ills of poverty. The idea seems fantastical. And, of course, invokes well-argued discussion. Unsurprisingly, a lot of work has been done on this idea around the world.

Before getting into the details, let me tell you a story.

Nelle’s Story

There was a young woman called Nelle, from Alabama, who wanted to be a writer, and she moved to New York in 1949 to pursue her dreams. Unfortunately, unless you’re famous, being a writer does not pay the bills, so she took a job as a part-time clerk at an airline to support herself. For 7 years, she continued writing but without any significant success. In 1956, she was still doing her part-time job, and she spent Christmas with a family she was close to. They were also a young family, with 2 children, and a little better off financially than her, but not rich. On Christmas day, they gave her a gift: a cheque worth one year of her salary. They wanted to help her to focus on her writing for one year.

She quit her job and used the Christmas gift to survive. She finished the first draft of a novel by the spring of that year.

Nelle’s full name is Nelle Harper Lee. And the novel is To Kill a Mockingbird, which went on to sell 30 million copies in 40+ languages. She won a Pulitzer Prize. And in polls by US/UK librarians the book is regarded as one of the “most influential books”, next to the Bible.

Would this have happened if she hadn’t quit her job?

How many Nelles in India never pursue their dreams because of finances?

Existing Schemes

When I first heard about UBI, it sounded to me like an ultra-idealistic fantasy—great in theory but impractical in practice, like communism. However, all over the world, there are various successful schemes which can be viewed as the first steps towards UBI. This includes the most capitalistic countries of the world, as well as developing countries like India.

US considered various proposals related to UBI in the 60s and 70s and finally implemented versions limited to groups of people—senior citizens, unemployed, disabled people, etc. Other countries have schemes for specific types of expenses. The UK and many other western countries, for instance, have universal free healthcare.

India has the MGNREGA scheme that guarantees 100 days of paid work for every household in rural India. And the Public Distribution Scheme (PDS), popularly known as “ration”, which provides subsidized food grains and fuel to two-thirds of India.

There are several other schemes all over the world.

UBI is different in that it proposes giving money—not food, or healthcare, or some other good or service—to everyone without any restrictions or conditions attached.

Why Everyone and Why Money?

How does it make sense to give money to everyone, without any conditions on how it is to be used?

For starters, giving money without any conditions significantly reduces the amount of expense and effort required in implementing and administering the program. It also reduces the potential for corruption. Two big wins, right there, without any costs.

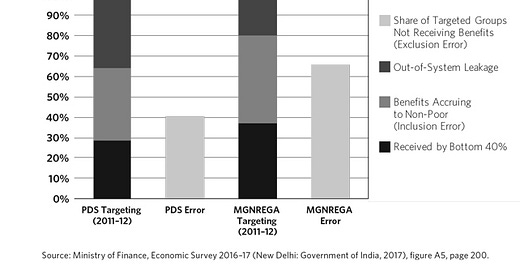

Consider this chart showing mismanagement in MGNREGA and PDS in India. As you can see, this is the government’s own data. A large chunk of the benefits goes to ineligible people. Another large chunk “leaks.” The lightest grey bars are people who should have gotten benefits but did not. Double whammy. If everyone got a UBI, these errors are taken care of. Although the data is from 2011-12, it was included in the 2017 Economic Survey of India, and there is no reason to believe that the percentages have changed significantly in recent times.

All of this would become seamless and would significantly reduce leaks if there were direct transfers of cash into the bank account of all citizens, for example, via the JAM trinity in India.

The UBI money transfer is unconditional because poor people are quite capable of making good decisions on how best to use the money for themselves. Any centralized scheme is suboptimal because it doesn’t know local conditions, changing situations, and cannot be tailored to the unique requirements of individual families.

Most often, the actual needs of the poor go beyond or are different from what the system has decided for them. In Poor Economics, Nobel Prize winners Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo describe a meeting with a man who didn't have enough money to feed his family but had a TV and a DVD player. When they pointed this out, he laughed and said, “Ah, but television is more important than food.” This incident changed their mind completely about how needs of the poor should be worked out.

No one, for example, should get to decide whether a family should eat rice or wheat, just because they are poor. Or that they must spend on food before they spend on entertainment. Unconditional cash transfers give a choice and dignity. A choice and dignity that you and I have. Read this article for more details and references.

The Case for UBI

Morality: It is inhuman to let people starve and live in abject poverty when the world can afford to prevent it.

Economical: If the poor are not poor any more, they can contribute far better to the productivity of the nation.

Social: In the last 50 years, the world has been getting better on almost all social indicators except income and wealth inequality. We are living longer and healthier, fewer children are dying. However, inequality has been increasing. Reducing inequality will have direct benefits and indirect ones, like maintaining social harmony. If people are content with their lives, they are less likely to fight with their neighbors or a neighboring country.

Justice: Why should the natural resources of the earth be denied to some people? Why should some rich people monopolize the resources because their ancestors managed to grab them by force? At the very least, we should allow a certain minimum amount of earth’s resources to be accessible to every human.

Whatever the reasons for supporting UBI, a look at the potential list of benefits is quite instructive:

Managing automation: As artificial intelligence technology matures, more and more tasks will get automated, there will be serious upheavals in jobs and livelihoods. Some people believe that AI will result in widespread unemployment, but others think that AI will create as many or more new jobs. Even in the latter, happier scenario, millions of people will lose their existing jobs and need reskilling before they can get new jobs. Poor people cannot afford to spend the money or time for reskilling. In situations like these, UBI would go a long way to ensure that this transition happens smoothly.

Gender Equality: There are many ways in which UBI can enhance gender equality. Many women endure abusive relationships because they aren’t financially independent enough to get out of the relationship. Even when the relationship isn’t abusive, just having an independent income makes it easier for women to be more assertive in their homes. Studies show that introduction of UBI results in increased participation of women in financial and non-financial decision-making at home, and activities outside.

Similarly, it can be argued that UBI will help reduce racism and casteism.

Breaking the poverty trap: To get out of poverty, a family needs education, or capital, or connections. Most poor families don’t have access to any of these precisely because they are poor. This cycle is difficult to break. UBI helps to break this cycle.

Improving capitalism: Because UBI gives poor people a fallback option, it increases the bargaining power of workers against their employers. This capacity ultimately results in improved working conditions and power dynamics.

Improving productivity: UBI will allow more people to focus on things that they are good at and/or enjoy doing. Instead of working on low-quality, low-skilled, dead-end jobs, UBI will empower entrepreneurial spirit and encourage arts. Even if a tiny fraction of the entrepreneurs and artists succeed, it will be a tremendous boost to the overall productivity of the world.

Objections to UBI

People will just spend it on alcohol and drugs.

Free money makes people lazy.

If people get more money, it will result in inflation.

Where will the money come from?

It will never work in a large poor country like India.

Let’s take the last one first.

UBI in India

In 2011-2012, UNICEF and SEWA, a self-employed women’s association conducted a UBI pilot program in Madhya Pradesh. They picked 20 similar villages, randomly chose 8 out of those for the UBI pilot and the remaining 12 villages served as a control group. For 18 months, every adult in the village was given ₹200 per month, and every child was given ₹100 per month. This amounted to 20%-30% of the average household income there. They measured changes to several social and economic factors in the UBI villages and compared those changes against the control villages.

Here are some of the eye-opening findings:

Alcohol consumption? None of the UBI villages showed an increase in alcohol or tobacco consumption. A few villages showed a decrease.

Laziness? The amount of time spent on labor and work increased.

Economy? 73% of the households reduced their debt or increased savings. Also, since everybody in the village had a little extra money, people could borrow from their friends, instead of borrowing from professional moneylenders who charge ridiculous interest rates. As a result, not only did the debt decrease but also the total interest payments decreased.

Productivity? People in the UBI villages were three times more likely to start a new business or add a new production activity in an existing business. 30% of the women switched from doing wage labor to running their own business. For example, Tulsabai saved some money, took a loan and bought two buffaloes. She used the milk from the buffaloes to make khoya (condensed milk) and sell it to a sweet shop. She didn’t need to engage in wage labor at all.

Agriculture: Overall spending on agricultural inputs (seeds, fertilizers) increased, resulting in increased yields.

Education: Spending on children’s education increased. The number of children dropping out of school decreased. Sure, the family now had money to spend on education. But also, presumably, children were free to study instead of earn for the family.

Health: Having a steady income improves nutrition, reduces stress, and improves health in general. The number of people visiting the health clinic with illnesses decreased, people were more consistent with seeking medical treatment, and with completing the course of medicines prescribed.

Gender equality: Nutrition for girl children showed improvement. 54% of the women in UBI villages reported equal participation in household spending decisions, compared to 39% in the control villages.

Most importantly, a follow-up study five years after the pilot program ended showed that most of the improvements were long-term. A small fraction of the households had fallen back to their pre-pilot condition, mostly because of medical emergency-related expenses. The good outcomes for most of the households persisted.

Government Support for UBI in India

The 2016-2017 Economic Survey of India has a 40-page chapter making a case for UBI in India. After citing evidence in favor of UBI from all over the world, it points out that implementing UBI in India of approximately ₹7000 per year would cost us about 4.9% of the GDP. Isn’t that ridiculously expensive? It turns out that there are 950 different central schemes providing subsidies of various sorts—from MGNREGA and PDS for the poor, to the so-called middle-class subsidies on aviation fuel, train travel, and so on. Together these subsidies take up 3.7% of our GDP, and once there is UBI, it is argued that all other subsidies can be removed, so the gap is not significant. Besides, they estimate that the top 25% of the population can be convinced to voluntarily give up their UBI (as was done in the case of the LPG subsidy), further reducing the cost.

Another suggestion the survey made was partial UBI. A payment of ₹3200 per year to all the women would cost just 1.1% of the GDP and can be fully funded by removing the middle-class subsidies.

To cut a long story short, a lot of serious thought has gone into thinking about UBI implementation in India.

Support for UBI from Around the World

UBI pilots have been implemented in dozens of locations around the world, from first world countries like the US and Canada, all the way to the poorest of locations in Kenya and Namibia. Overall, here are some of the interesting findings:

Thirty studies in three continents and not a single one showed an increase in alcohol or tobacco consumption.

In Canada, UBI showed a small decrease in the number of work hours (less than 5%). Further analysis showed that this was owing to new mothers choosing to stay home with their infant, or teenagers choosing to stay in school instead of working to supplement the family income.

In a pilot in Namibia, over two years, the number of families below the poverty line fell from 73% to 37%, the number of 15+ year-olds engaging in income-generating activity increased from 44% to 55%, underweight children decreased from 42% to 10%, school dropouts decreased from 40% to almost 0, and non-attendance due to financial reasons dropped by 42%. There was a significant increase in economic activity, including launches of many small businesses like brick-making, bread-making, and dress-making.

Cash transfer and gender: A review of 56 different cash transfer programs around the world found that “cash transfers can increase women’s decision-making power and choices, including those on marriage and fertility, and reduce physical abuse by male partners.”

Cash transfer and mental health: A number of studies show that unconditional cash transfer programs result in improved mental health outcomes among the poor, especially youth and children.

For me, the most interesting bit in the Namibian pilot was that each village in the pilot set up an 18-member committee of experienced people to guide villagers on how to use the money wisely. Local knowledge and understanding of local issues are essential elements in such cases. There is a lot of evidence that decentralization of decision making leads to better decisions.

So, why aren’t we UBI-ing the s*^t out of poverty? What’s the catch?

The Real Problems

As we’ve seen from some of the examples above, at least some of the objections to UBI might be overblown. People who receive UBI don’t actually spend it on alcohol and tobacco. People who receive such benefits from the government do not stop or reduce work.

Will UBI cause inflation? This is a fairly complex subject. Here is a must-read article which analyses the issue in detail. Any simplistic understanding of this issue is most probably mistaken. For example, people feel that there will be inflation because the same goods and services are now being chased by more money. However, when there is UBI, money isn’t being created, it comes from taxing the wealthier people, so it is the same amount of money, just distributed differently. Further, the number of goods and services aren’t the same. As we saw earlier, economic activity and productivity increases. As a result, in reality, it is likely to be the same amount of money being used to buy more goods and services, and this shouldn’t really cause inflation.

I have spent much of this article talking about all the advantages of UBI and might have given the impression that the supposed problems with UBI aren’t real problems. However, all the things I said in the article are controversial. Despite various studies supporting the arguments I’ve made, you’ll find lots of people who disagree with each of them, pointing out that the studies are either too small, or too limited, or not really representative.

Here are examples of arguments against UBI:

UBI would make things worse for the poorest people by cutting down all the existing subsidies and programs that are helping them and replacing it with a benefit that is more spread out across the population

Although UBI on a small scale in poor villages has shown that it does not result in people becoming lazy, the same will not be true on a large scale, or in more affluent countries. It will discourage work and encourage a culture of people not taking responsibility for their own future.

People point to Saudi Arabia as an example which clearly proves that UBI will make people lazy. Saudi Arabia gets 90% of its income from oil and ensures that every Saudi has at least a basic income. Around ⅔ of Saudi nationals work for the government, and it is claimed that 90% of them do virtually nothing.

In developed countries, many economists believe that UBI would cost too much, and wouldn’t really solve all problems.

Some people feel that the recent increase in interest in UBI is because Silicon Valley is feeling guilty. It made so much money increasing inequality in the world, and things might get worse as AI starts taking away jobs of poor and middle-class people.

The most crucial problem is that UBI at scale is untried. No one has done a really large pilot, and no one has done a pilot that has lasted for a very long time. So, nobody really knows what will happen if UBI is ever implemented on a large scale permanently. If and when it is tried, there will be lots of challenges in ensuring that it works smoothly.

And most importantly, implementing UBI will require an increased tax burden on the tax-payers, and removing the existing subsidies and schemes. This will cause distress in sections of the population that oppositions can exploit. And the question is, which leader will have the guts to implement UBI?

Conclusion

This is a complex topic, and there are no simple and easy answers. But the reason I wrote this article is to make these points:

When I first heard of UBI, it sounded like a ridiculously impractical idea that couldn’t possibly be taken seriously. A closer look reveals that the idea is being taken quite seriously in lots of places, including India. And that it might not be so impractical.

Often, people first encountering the idea feel convinced that it wouldn’t work because the money would be spent on alcohol, or it would make people lazy. A look at the data indicates that this might not be true.

There was already worry that AI and automation would lead to widespread job losses and social upheavals. This has been further exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, UBI or UBI-like schemes are being taken more seriously around the world. So, we all should educate ourselves about this topic.

Acknowledgements

Edited by Meeta Kabra. Many thanks to Makarand Sahasrabuddhe and Meeta Kabra for reviewing drafts of this article, suggesting improvements, and providing references.

Next Steps

Don’t just click a button, do something. If you have comments or suggestions please let me know via email, or a comment below. If you think others would like this article, please forward it or share it on social media.

Hello! Did you see this study? https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/stocktons-basic-income-experiment-pays-off/618174/ Says much the same thing. https://www.npr.org/2021/03/04/973653719/california-program-giving-500-no-strings-attached-stipends-pays-off-study-finds. We need an India specific one though. And thought must be given to remove people's misconceptions like, free stuff means men don't work (though apparently, women do).

"A payment of ₹3200 per year to all the women would cost just 1.1% of the GDP and can be fully funded by removing the middle-class subsidies."

Uh, that's not a UBI. The most important element of implementing Basic Income in India would be to avoid the usual Indian oversmartness of carving out special groups or exceptions. Only then will it be a true UBI, only then will it really work. Otherwise it will turn into another leaking dole which will inspire bitterness in those who don't get it.