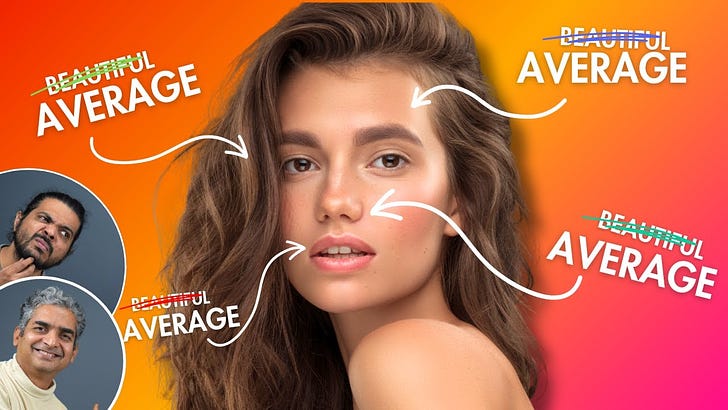

Media and movies and now Instagram are definitely trying to push a certain standard template of beauty (or more generally, attractiveness) upon all of us, but not everything about attractiveness is a construct of media—I was surprised when I first found out that there were aspects of attractiveness that had scientific and even mathematical backing.

Beautiful People are Average

Let’s start with a surprising one: the connection between being attractive and averageness.

(If you don’t want to read this article, it’s available as a video.)

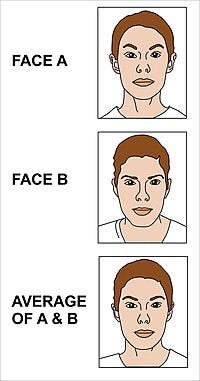

This was accidentally discovered by Francis Galton in the late 1800s. Being a bit of a biological racist, Galton felt that it was possible to just look at people and tell whether they were criminals. And he wondered whether it was possible to extract some common characteristics in the faces of all criminals. For this, he took several photographs of criminals and then superimposed these photographs on top of each other to create a composite “average” criminal face. This face was literally an average face, in the sense that the nose was mathematically the average of all the noses and the lips were mathematically the average of all the lips and so on. Unfortunately for Galton, this average criminal face did not at all look like a criminal. He tried the same thing with the faces of vegetarians with the same result—the average vegetarian didn’t look like a vegetarian.

So, Galton had to give up this theory, but he noticed that unexpectedly both these average faces were more attractive than any of the individual faces. (These average faces were more attractive than the average human. Haha! That sentence makes total sense if you follow the whole argument carefully. Sorry.)

Anyway, this was the discovery of the “averageness effect”: for many physical features, high attractiveness tends to be an average of the average traits among the population.

And don’t assume that this only works for unsavoury characters like criminals and vegetarians. This finding has been replicated by many other researchers in many different situations.

Deepika Padukone is Not Average

Media and Instagram props up celebrity role models that set impossible standards of beauty and there’s a generation of kids growing up with mental health problems because their own bodies don’t measure up to those standards. So clearly, being extremely attractive is very rare, and it seems paradoxical to say that attractiveness is average. How does one explain this?

The thing to realize is that in a population, there are lots of instances of values that are near the average value, but instances with the actual exact average value are rare. In a class, if the average score on an exam is 47.3, there will be lots of students in the 45 to 50 range, but most likely nobody would have scored exactly 47.3. And being exactly average on many different features is even more rare: A bunch of people might have an average distance between the eyes, and another bunch of people might have an average width of lips, and so on, but when you are very close to average on all those features, then you’re Jessica Alba.

Tall Men Are More Attractive than Men of Average Height

The averageness effect doesn’t apply to everything. When certain things directly increase chances of survival (in the African Savannah, where we all evolved), then having more of those is attractive. So tall and muscular men are more attractive. And so are women with wide (birthing) hips. But even that has limits—6 foot 2 is attractive, 7 foot 2 is less attractive.

So Why is White Skin More Attractive than Brown?

Our culture and media mess with our innate concepts of attractiveness.

Researchers at Harvard University went to Tanzania to find an isolated tribe Hadza people (i.e., a tribe that hasn’t been exposed to Western media) and averaged the faces of 1000 of them. The Hadza people found the average Hadza face attractive. However, they did not find an average European face attractive.

Finding averageness attractive is hard-coded in our genes. But later culture and media overwrite this base preference with a bunch of modern constructs. It is quite likely that the “thin and fair” stereotype of attractiveness is a modern creation. You’ll notice that all the women in Renaissance paintings of medieval masters would be fat-shamed out of the studio today. There is even a word, Reubenesque, to describe that kind of beauty, which is no longer preferred.

How Do We Know Averageness Is Genetic?

There’s research. Here are some interesting research findings:

Attractiveness is biological: Babies look at attractive faces for more time than other faces.

Averageness is biological: Babies respond to averaged faces in the same way that they respond to attractive faces.

The above is true even if we use just hand-drawn sketches of faces with just 4 features.

How do babies learn to find average faces attractive? There’s research showing that newborn babies (15 minutes after birth) show no preference for attractive faces. However, 1-day old babies start showing a preference. It is believed that babies brains are hardwired to average the first 30 faces they see and then find that attractive for the rest of their lives (until Instagram overwrites this somewhat)

The Evolutionary Reasons for Attractiveness

Why do we find averageness attractive?

Ultimately, being attracted to mates with average features is an evolutionary advantage. Darwin’s theory states that characteristics that confer advantages in survival will replace characteristics that don’t, and so, over time, the prevalence of characteristics in a population will increase. In other words, evolution teaches you to prefer mates with the least number of unusual characteristics: i.e. those with the most average features.

There are other aspects of attractiveness that are also explained by evolution and fitness.

We like symmetric faces more than asymmetric ones because it indicates that you have good quality genes that are able to maintain the symmetry in the face of environmental disruptions while you’re growing up.

Similarly, in women, an hourglass figure (with a waist-to-hip ratio of 0.7) is preferred because certain female hormones—that are correlated with fertility—give that shape. But this is not true always and everywhere: in some cultures, where women need to work to find food, having an hourglass figure would be a disadvantage and as a result, in those cultures a higher waist-to-hip ratio is preferred.

So What?

So nothing. There is no moral of the story today, no life lesson to learn. I just found these ideas fascinating and thought I should write about them.