Two Brains, One Team: System 1 and System 2

Understanding and using your lizard brain and human brain effectively

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” ―Carl Jung

All of us have two brains: One is the lizard brain, the part that evolved hundreds of millions of years ago and controls our instincts, our emotions, and much of our social behaviour1, and the other is the advanced, logical, rational human brain, just 2 or 3 million years old, that we use for language, and jokes, and Excel spreadsheets, and strategic thinking, and making devious plans. We humans are very proud of the rational brain. But we don’t realize how much of our life and behaviour is controlled by the lizard brain and how the rational brain convinces itself (and you) into thinking it is in control.

This article, based on ideas from the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, is about helping you understand the strengths and weaknesses of these two brains, the surprising pitfalls when the wrong one is used for a task, and how to avoid these pitfalls. (Technically, these are two modes of thinking, and Kahneman refers to them as System 1 and System 2.)

The content of this article is also available as FutureIQ YouTube video, if you prefer video:

or as a FutureIQ podcast, if you prefer podcasts:

Thinking, Fast and Slow

To understand the difference between the System 1/Fast/Lizard/Reptilian+Limbic brain and the System 2/Slow/Human/Rational Brain (neocortex) look at this image for just one second:

What can you tell me about this image? You may have noticed that the woman looked like she is either angry or going to shout at someone—as if her husband put too much salt in the eggs and now the kids won’t eat it. The fact that you were able to make all these assumptions about the woman in just one second without even putting any effort or focus into it is thanks to your System 1 brain.

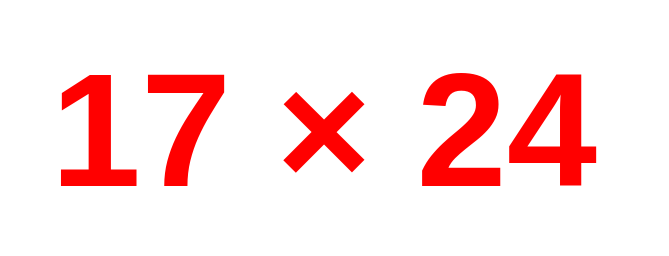

Now, look at this other image:

What can you tell me about this? You can see that this is asking you to do a multiplication but you don’t know the answer. If I were to give you a pen and paper, you would be able find the answer, but it would take you a while to do it. That's because when our brain evolved, in the African Savannah when we were hunting deer and running away from wolves, multiplication was not a thing. Hence your System 1 cannot handle it, and this is left to your System 2, the human brain, which is much slower and a later evolution. It takes effort and concentration and time to use System 2.

What are System 1 and System 2

Take a look at these two lists of the capabilities of System 1 and System to (from Thinking, Fast and Slow, via Wikipedia):

System 1: Fast, automatic, frequent, emotional, stereotypic, unconscious. Examples (in order of complexity) of things system 1 can do:

determine that an object is at a greater distance than another

localize the source of a specific sound

complete the phrase "war and ..."

display disgust when seeing a gruesome image

solve 2+2=?

read text on a billboard

drive a car on an empty road

think of a good chess move (if you're a chess master)

understand simple sentences

associate the description 'quiet and structured person with an eye for details' with a specific job

System 2: Slow, effortful, infrequent, logical, calculating, conscious. Examples of things system 2 can do:

prepare yourself for the start of a sprint

direct your attention towards the clowns at the circus

direct your attention towards someone at a loud party

look for the woman with the grey hair

try to recognize a sound

sustain a faster-than-normal walking rate

determine the appropriateness of a particular behavior in a social setting

count the number of A's in a certain text

give someone your telephone number

park into a tight parking space

determine the price/quality ratio of two washing machines

determine the validity of a complex logical reasoning

solve 17 × 24

Depending on what we’re trying to do and how much time we have to do it either System 1 or System 2 takes control of accomplishing the task. Realizing within seconds of seeing your that she’s angry is System 1’s doing. Deciding that you’ll send her flowers to make up for this is System 2.

When Do We Use System 1 vs System 2?

So, what decides when System 1 or System 2 is in control? System 1 is always on, and it's usually the first to react to any situation and decides whether it can handle it. It deals with emotions, stereotypes, and instincts (anything that herd animals are capable of). System 2, on the other hand, takes a conscious effort to engage and is responsible for logical thinking and complex problem-solving and is only called in when necessary. For example, when you see a shady-looking person coming towards you on the street, the fact that you have already decided that person is shady has come from your System 1 brain, and you are not really in control of it. Later, System 2 can slowly decide what you’re going to do about it: maybe you’ll cross to the other side of the street, or maybe you’ll chide yourself for thinking in stereotypical terms.

In most situations, System 1 is perfectly capable of handling things. For example, when you're driving a car, you don't consciously think about every action you take. System 1 is fast and can react in 0.1 seconds whereas System 2 doesn’t even get started for 0.7 seconds. You have to rely on your System 1 brain to handle the automatic functions, such as steering and braking—if System 2 was doing it all, you wouldn’t be able to drive.

In parallel, System 2, working slowly and methodically is using all its complex machinery, its system of logic and rational thinking, and its lists of pros and cons, to take a few additional high-level decisions. Thus System 2 can choose when and where to merge into the traffic on a highway when changing lanes, or it can decide to increase the distance between your car and the one ahead of you because that driver is driving erratically. It is important to note that while System 1 can handle a lot of things simultaneously (steering, accelerator, brake, reacting to sudden movements by things on the road) System 2 has a very limited capacity and can usually only handle one decision at a time. You can do both, chew gum and think, at the same time only if System 1 is handling the task of chewing gum.

System 1 and System 2 Working as a Team

Everything works best when Systems 1 and 2 work together as a team. Let me give you an analogy: suppose you wanted to go across town at a high traffic time, and you have two people—one is an experienced old-time driver who can drive well and weave through traffic but doesn’t know the roads of this city well, and the other is a non-driver who knows how to use Google Maps well.

The best way to get across town is for the Google Maps person to decide which route is the best, and then the driver to weave through the traffic and get there fast. Either of them by themselves wouldn't do as good a job. So, the driver is your System 1, and the Google Maps person is System 2. System 2 takes a few high-level decisions while System 1 does the second-to-second handling of hundreds of tasks without the involvement of System 2.

Strengths of System 1

An important thing to remember is that System 1 is really good at what it does. Remember the photo of the woman from earlier in this article? Was her hair dark? Was she Chinese? I can ask you 5 more questions like these about her and you’ll be able to answer them easily without having to even look at the image again. Because your System 1 remembers it all (for a short while2).

Another example: Consider this photograph. You are standing where the camera is, and you have to cross this street. Can you cross just before the two two-wheelers? Or maybe cross just after the two-wheelers but before the rickshaw?

Without really thinking about it, you make quick judgements like these every day. If you try to do the actual calculations mathematically, you will probably need calculus and second-degree differentials to solve this. If System 2 had to take all these decisions, with its 0.7-second reaction time—especially given the fact that most people can’t do 17×24 in their head—people would be dying in the streets every day. But System 1 handles this all effortlessly while still leaving your System 2 free to check WhatsApp. (Why? Because 1) large bodies moving towards you at various speeds, and 2) you having to judge your speed against their’s, and 3) calculating an interception course, were all important skills when you were the hunter and the hunted in the African Savannah.)

System 1 can handle even more complex situations. For example, a lot of women sometimes get a vague uncomfortable feeling about some men, which makes them feel unsafe around them, and want to avoid contact with those men. They can’t really explain why they have this feeling—just that they have it. Some of them even have stories of how this later turned out to be justified, because they later heard stories of shady behavior of those men. There might be a few unfortunate stories of women who ignored this instinct and later got into trouble. This is System 1 matching some complex pattern and raising an alarm. It can sometimes be wrong but can often be correct. (Remember, System 1 handles social behavior and helps distinguish friends from foes, an important survival ability in the African Savannah.)

Here’s another example, from Thinking, Fast and Slow:

The psychologist Gary Klein tells the story of a team of firefighters that entered a house in which the kitchen was on fire. Soon after they started hosing down the kitchen, the commander heard himself shout, “Let's get out of here!” without realizing why. The floor collapsed almost immediately after the firefighters escaped. Only after the fact did the commander realize that the fire had been unusually quiet and that his ears had been unusually hot. Together, these impressions prompted what he called a “sixth sense of danger.” He had no idea what was wrong, but he knew something was wrong. It turned out that the heart of the fire had not been in the kitchen but in the basement beneath where the men had stood.

When things go wrong

An example of System 1 doing System 2’s job: A common way for things to go wrong is for System 1 to take decisions which really should have been taken by System 2. Consider this question: A ball and a bat together cost ₹110, and the bat costs ₹100 more than the ball. How much does the bat cost? Most people who encounter the question for the first time answer ₹100. That’s a System 1 answer—System 1 mistakenly decided that the question was easy enough for it to handle. But once you involve System 2, you’ll realize that the real answer is ₹105.

An example of System 2 misleading System 1: One of the important jobs of System 2 is to let System 1 know where to direct its attention3. Consider the video below. Watch it carefully and count how many times the players wearing white pass the basketball. First, do that before continuing…

There’s a large number of people who completely miss the gorilla! Why? Because System 2 insisted that all the focus should be on counting the number of passes by players in white.

Obviously, the above examples are both contrived and situations like these are not likely to happen in real life.

Right?

Wrong. A lot of sales, marketing, and advertisements exploit the confusion between your System 1 and System 2 to influence your decisions without you realizing it4. For example, a car ad might show a new car with a hot model next to it while the voiceover talks about the features of the car. You think you’re making a decision based on the practical and pragmatic reasons in the voiceover but often, what’s happening is that your System 1 is thinking, “Hmm… If I buy that car, I would be next to that car, in which case I would be next to that hot model…” At this point, you don’t realize it, but System 1 has decided that it wants the car and is instructing System 2 to manufacture rational reasons why it makes sense to buy it. (Thinking through why System 1 does this is left as an exercise for the motivated reader.) System 2 might, ultimately, decide to not buy the car because the logical reasons are overwhelming, but you’ll be very unhappy about it.

In general, a lot of people, from advertisers to politicians to godmen are experts at hijacking your System 1 without you realizing it.

Unless you’re extra careful, you’re going to fall for these tricks.

Can you change System 1’s behavior?

Imagine a cricket match. James Anderson bowling to Kohli. Kolhi fishes outside the offstump to an outswinger and edges the ball to the wicket-keeper and one billion people groan, “Why can’t he leave those balls outside the off?!?” By now, even Kohli is aware of the fact that fishing outside off is one of his weaknesses, so why doesn’t he stop?

The problem is System 1. A fast ball reaches a batsman in less time than the 0.7 seconds required for System 2 to make decisions. So the decision of whether to leave or attempt a stroke is taken by System 1. (Ability to judge the path of projectiles thrown at you was obviously important in the African Savannah.) And System 1 is not easy to change. It took Kolhi years of practice to perfect his batting reactions and unlearning one part of it (the fishing outside the off) isn’t easy without breaking other things.

Making System 1 learn things can be done: it takes a lot of deliberate practice. We’ll cover this—along with the benefits of rote learning—in future articles. Making it unlearn bad habits (like fishing outside the off stump) is harder.

TMKK

So what is the takeaway message from all this?5

Be aware that System 1 is in charge: that a lot of your decisions are being taken by System 1 and then System 2 is later creating plausible reasons to support System 1. So introspect and ask yourself what are the real reasons why you’re doing something. Mindfulness is popular these days and some of its power lies in bringing System 1 decisions to the attention of System 2

Don’t shortchange System 1: Don’t assume that everything System 1 does is biased or mistaken. You can’t function without a functioning System 1. There were good reasons for System 1’s heuristics, at least in the African Savannah. Now the world has changed, some of them are no longer applicable. But not everything has changed—so the System 1 heuristics might still be applicable (identifying creepy men) or not (hot models in ads). You have to identify the few situations when they are not applicable and train yourself to override your System 1 in those cases. But let System 1 do its thing in all other cases.

Teach System 1 new tricks: As long as you’re willing to put in the right kind and quantity of effort, System 1 can learn new things. Kolhi wasn’t born with all his glorious cricketing shots (the ability to hit a cover drive is, sadly, underappreciated in the African Savannah). He got it through thousands of hours of practice. System 2 has very limited capacity. So pushing things down to System 1 (via deliberate practice) increases what you can do and frees up System 2 to handle even higher-level things. This is why rote learning is important and necessary in school if done right. I’ll do full articles on deliberate practice and habit formation at some point in the future.

Be Kind: System 1 is not easy to change, so be kind when you see examples of people behaving in ways that you think are problematic. You are analyzing those using your System 2 but probably they took those actions under the influence of System 1, which is not easy to change. Also, keep in mind that this person might be you: so be kind to yourself when your System 1 is unable to stick to the discipline decided by System 2 thinking. Making a New Year’s Resolution is a System 2 change that is trivially easy. Sticking to the resolution is a System 1 change that takes huge amounts of effort.

What do you think? Please let us know in the comments.

Programming Note

I’m rebooting this newsletter after a long break. This time, posting is likely to be much more regular, hopefully at least once a week if not more. In addition, each article is likely to also be posted as a YouTube video and a podcast (just like this one). Please forward this article to others you think might like it or use the Share button below.

I’m playing fast and loose with the terminology here. Technically, scientists divide our brain into 3 parts. The reptilian brain, the oldest part, handles basic instincts like breathing, heart rate, and survival instincts (including quickly withdrawing your hand if it touches fire). The limbic brain, a little newer, handles emotions and feelings and social behaviour. The neocortex, the rational brain, just 2 or 3 million years old handles higher-level thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making. It is the part of the brain that makes us uniquely human. For the purposes of this article, I’m mixing the first two parts into what I’m calling the “lizard” brain. Also, probably the term “brain” is also misleading. Kahneman refers to them as “modes of thinking” and calls them “System 1” and “System 2”.

How long your brain remembers things is controlled by something called the forgetting curve. This is a fascinating and important topic which plays a big role in learning and using it effectively is an art and an app. I’ll cover this in a future article when talking about spaced repetition memory systems.

People following the latest advances in AI and Machine Learning would recognize how important the concept of “attention” has been in the last 5 years.

Influence, by Robert Cialdini, considered a seminal work in the area of sales and marketing psychology, is full of techniques like these.

TMKK means “Toh MaiN Kyaa KarooN?” i.e. Why should I care? (I’ve stolen the idea of having a TMKK section in all my articles from Ashish Kulkarni.)

Brilliantly articulated Navin. I don’t think it could have been made simpler than this. The examples are the cherries that add to the flavour of the article.

Brilliantly written Navin. I will work on capacity of System 1