Why Is There So Much Incompetence: The Peter Principle

How Sensible Policies Guarantee Widespread Incompetence

Written by Arsh Kabra based on my notes.

We are surrounded by incompetence, and it is increasing. Surprisingly, this is by design—we are doing this to ourselves.

Incompetence is Everywhere

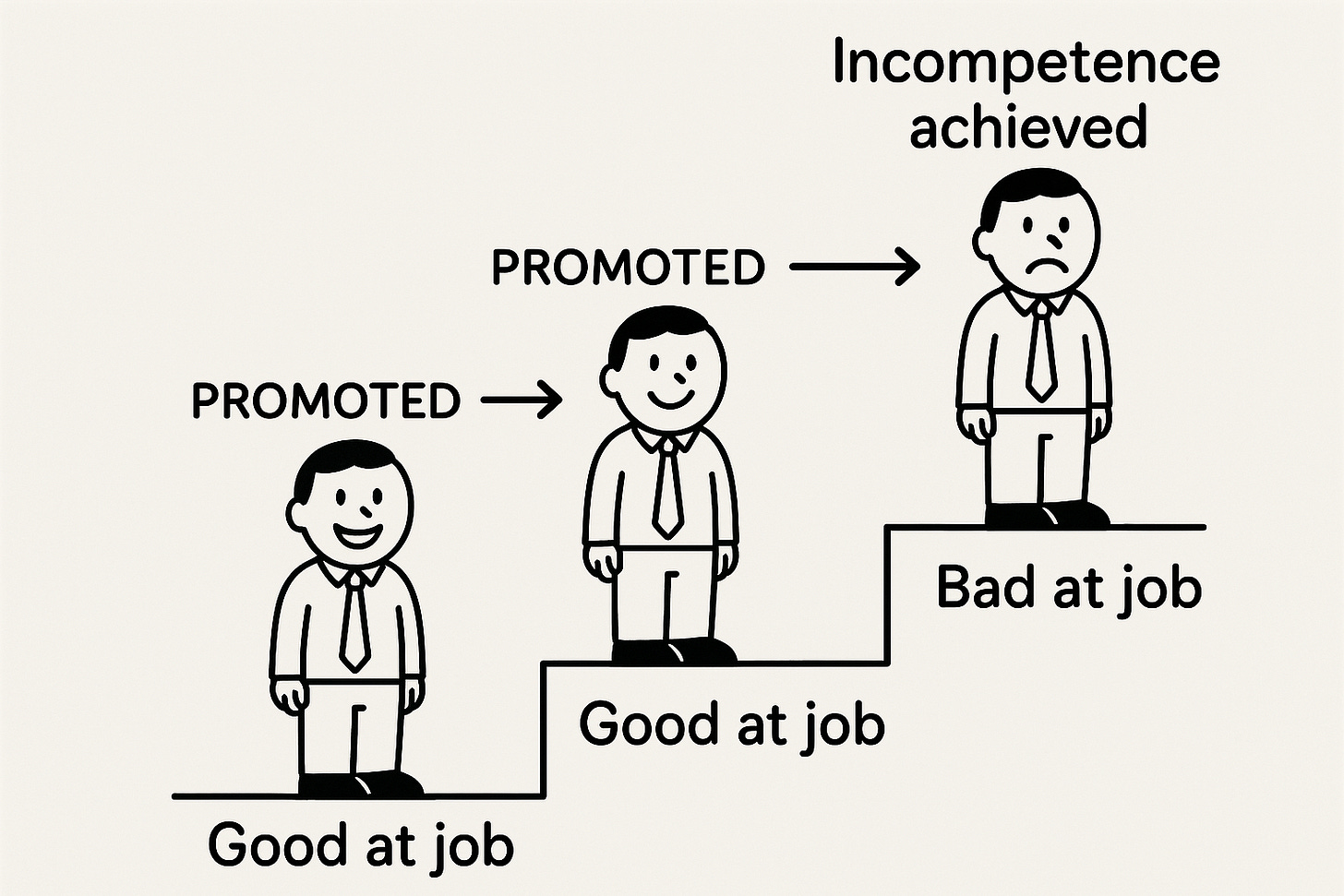

Imagine a software engineer who’s good at her job. This is noticed, and soon she’s promoted to being a manager. Being a good software engineer has little to do with being a good manager of other software engineers. The latter job primarily involves managing people and their strengths and weaknesses and egos. A manager who used to be a good software engineer has a good understanding of what her subordinates should be doing, but this can sometimes be a disadvantage in the new role. So now, it is easy to imagine that this new manager could be bad at being a manager. The most likely outcome of this is that she’ll never get promoted after this and will stay in this role for a long time, doing it incompetently. If she ever learns to do this job well, she’ll get promoted to something else that she is probably bad at.

What happens if this happens with all the people in all the companies? People good at their current roles get quickly moved up. And those bad at their current roles stay there forever. The logical outcome of this is that most people working in companies will be bad at their current roles.

This is called the Peter Principle, and it affects more than just managers. It affects the biggest businesses in the world, and could also affect you in ways that you may not at first realize.

Canadian educator Laurence J. Peter came up with the Peter Principle, which states:

“In a hierarchy, every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence. In time, every post tends to be occupied by an employee who is incompetent to carry out its duties.”

As long as people are competent, they keep rising (quickly), and when they reach a point of incompetence, they do not rise any further—it’s Game Over. You rise to your level of incompetence.

This is a lot more prevalent than you might believe. It’s what happened to Microsoft. In the early 2000s, Microsoft, under CEO Bill Gates and COO Steve Ballmer, had become the most powerful company in the world. A lot of the credit for this goes to Steve Ballmer, who was an excellent salesperson and COO. When Bill Gates retired, Ballmer went from being the COO of Microsoft to the CEO. When Ballmer became CEO, however, his success, shall we say, left something to be desired. Under him, Microsoft missed the mobile revolution and the cloud revolution and stagnated, only recovering after Satya Nadella took over.

But perhaps that’s just an isolated incident. How common can this really be?

In 2018, research was conducted on 214 American businesses. They looked at what was taken into account when promoting employees, and how the promoted individuals did at their new jobs. Across the board, the reason for promoting employees was “competence at current role”. Not “potential competence at the new role.”

This sounds normal, but take a second to think about this. We see someone doing good work in a certain role, and what we do is equivalent to, “You know what, this person is good at this. We need to move them to something that they’re bad at.”

And the research also showed that those promoted were more likely to perform badly in the new role.

How Do We Fix This?

Aptitude Tests?

Seems pretty obvious: We evaluate potential promotion candidates for their aptitude for the new role, of course!

Alas! If only it were that easy.

In some companies, there is an interesting problem: they give you an aptitude test to get an idea of which role you are the most competent at, and you are directly put there. This means, you have nowhere to go from there—your aptitude for all other roles is worse, isn’t it?

In any case, most companies don’t use objective tests when deciding promotions. Usually, managers and other senior staffers evaluate you. But hey, guess what? Laurence J. Peter has a few things he’d like to say about those managers and other senior staffers. They’ve already risen to their level of incompetence! They are likely to be incompetent at evaluating you too.

And most important is the fact that the key skills required for higher roles in businesses cannot be tested. Things like how you manage stress, how you make decisions in crisis situations, whether you have the personality of a leader… These things are nebulous and untestable.

Take, for example, the research of the Nobel Prize-winning Economist Daniel Kahneman. He and his team studied soldiers in the Israeli Military. They conducted an intensive two-week boot camp, testing whether or not soldiers would make for good officers in the military. As time went on, the researchers tracked the soldiers’ actual career paths. Do you know what they found?

[T]heir forecasts proved "largely useless" in the long term. Comparing their original evaluations of candidates with the judgments of their officer-training school commanders months later, Kahneman and his colleagues found that their own "ability to predict performance at the school was negligible. Our forecasts were better than blind guesses, but not by much." (source: Wikipedia)

This is called the Illusion of Validity. Standardised evaluations and tests cannot measure some of the things that make someone a good leader or manager but we all believe that they do without looking at the data. The few people who’ve looked at data, like Kahneman, and Google(!), found zero correlation.

Why Don’t They Upskill Themselves?

When someone realizes that they’re incompetent at their job, why don’t they do something about it? Like upskilling themselves?

Unfortunately, because of the Dunning-Kruger effect, there’s a high chance that anyone incompetent at a role will not realize this. They think they’re doing a good job. They will, however, realize that things aren’t as well-oiled as they used to be earlier, when they were in a role that they were good at. They see new people in their earlier role and blame all the problems on them instead.

Up Or Out?

One interesting approach to this problem comes to us from McKinsey & Company. They have what’s called an “Up or Out” system. If you’ve been working with them for two years and you have not been promoted yet, you will be asked to leave. It ensures that people who’ve risen to their level of incompetence can’t stay there for more than two years.

But most companies find this too drastic.

Randomizing Promotions?

Another radical idea suggested by research is randomising promotions. The idea is to take the best employee and the worst employee and then basically flip a coin to decide which one gets promoted. The idea is that even the worst employee at a certain job may be good at the next one up. Seems a bit ridiculous but the research claims that this is might be better than the current systems.

The idea of using randomization instead of merit is a very old one and is called “sortition”. It was used to appoint political officials in ancient Athenian democracy and it is used even today all over the world to pick juries for court trials. There isn’t any clamour for a merit based system to pick juries, is there?

This idea has been also been floated for the IIT JEE exam. The proposal is that you have a basic cutoff of a certain rank or score which should not be a very tough exam like the current JEE. After that, use a lottery to see which college students get into which college. This would get rid of a lot of the stress of the JEE, because you can’t study for a lottery. And, more importantly, there are good arguments to indicate it will not produce worse results than the current system.

It doesn’t matter. This is politically impossible to implement, so it will probably never happen.

What Should I do?

Fixing things at an organization level is not easy. But what about your own career. What can you do to not fall into this same trap yourself—right now you might be in a role you’re not a good fit for, and you might not even know it, right?

How do you find out if you’re not good at your current role? Look for indirect signs of your incompetence. If you’ve been feeling more stressed at work or if you’re constantly complaining about how the past used to be better, do a little self-reflection. If it appears as if a large number of people around you have gotten worse at their jobs since you took on a new role, then the problem might be you.

When I was promoted to a managerial role from individual contributor, I quickly I realized that I not enjoying myself (and was probably incompetent at it). Within 6 months I went back to being an individual contributor.

But self-demotion, or even premptively refusing promotions to avoid this fate, is a bad idea in general. That helps nobody—neither you, nor your workplace. If you do that you will never grow as a person and a professional. It is also against your financial interests. (I should point out that the Peter Principle book says that refusing promotions is a bad idea “especially if you’re married” because your spouse/family will not be happy with your self-goal). Anyway, try new things. It always helps, even if you’re not good at some of them.

So, you power through. And constantly be on the lookout for ways to upskill yourself. For this, you have to try and identify the few competent people you know who’ve done the thing you’re current doing (and might be incompetent at) and learn from them.

Think about it: when you are new to a role, you should be upskilling yourself because you’ve been given new responsibilities that you’re just picking up. And when you’ve been in a role for a while, you should be upskilling yourself even more desperately, because it is a sign that you might be bad at the role. In other words, Always Be Learning.

Summary

I’ve been painting an unnecessarily pessimistic picture. The world isn’t so bad. At any given time, there will be a lot of people who are competent in their role and haven’t been promoted yet because it hasn’t been too long. And the people at the top might not have this problem even if they’ve been in their role for a long time—there’s nowhere else to be promoted. And smaller companies usually don’t have this problem: they don’t have too many levels, and if the people at the top are not competent, the entire company dies. (In a capitalistic society. If government rules prevent a company from dying then there can be widespread incompetence.)

But it is important to be aware that the larger and older an organization, the more the chances of there being widespread incompetence. Just because someone is “very experienced” don’t assume they’re competent. And, there aren’t any great solutions to this problem at an organizational level.

So, on a personal level, it’s important to stay vigilant. Look for hints that of your own ineffectiveness. If you’re not going up, then see if you can move sideways to a role that plays more to your strengths. And, always be learning.

If all of us at the very least try to get more competent at more things, perhaps we can start turning this thing around.

About the Writer

Thanks to Arsh Kabra for writing this article based on my notes because I’ve not been getting the time to do that myself. Arsh, who is my son, is a freelance writer who lives and breathes stories. Whether it’s scripting for YouTube channels, running epic Dungeons & Dragons adventures for young minds at Flourish School, or bringing plays to life on stage, he’s always finding new ways to spark imagination--both for himself and anyone else he can get a hold of.