Why Women in India Don't Work?

We have the worst rates of female labour force participation, and obvious solutions don't work. So what does?

Written by Arsh Kabra based on my notes. You can choose to watch my video/podcast on this topic.

India has one of the worst rates of female labour force participation (FLFP) rates in the world. We are at 30%. Even Bangladesh is at 40%. There’s no point in even comparing with China, which is at 71%. Women's contribution to the Indian GDP is 17%. The global average is 37%. Fixing this will result in economic growth, poverty reduction, and improving the status of women. But it’s not easy.

I’m sure you aren’t surprised to hear that women don’t make up much of the workforce in this country. I’m sure you’re also not surprised to hear that it’s vital that their number increases. What is surprising, however, is how much worse India is than the rest of the world. It’s a big problem that leaves a lot of work still to be done and that has its roots deep in our psyche as a nation.

You may already have heard of some things that might fix this issue. But many of these fixes are surprisingly ineffective. The things that actually work might not be what you expected.

How Bad Can It Possibly Be?

Quite bad, actually.

Here’s a map of the world showing you how many of the world’s women are working. As you can see, we are quite a few shades away from the blue in our cricket jersey. Bangladesh bleeds bluer than us when it comes to this issue. India’s number is somewhere around 30%, whereas Bangladesh has 40%, and Indonesia and the Philippines score 50%.

Check out this worm graph, too, showing you how low it’s gotten over the years.

This problem is bad everywhere in the world—50% isn’t a great number either. But it’s especially bad in India.

Why Should Women Work?

An IMF report suggests that if women joined the workforce, we’d all be about 30% richer. More specifically, it says that it would increase India’s GDP by about 27%. And that’s not just rich people hoarding money, that’s a quality of life upgrade for everyone.

Not to mention that it would make women’s lives better. Financial independence would mean that women have more power in their households, and more freedom to act as they wish. It’s also shown to decrease the threat of domestic violence.

Just a good deal, all things considered.

But Women Belong in the Kitchen!

But this does bring us to an important point about why this problem exists, and how we got into this situation in the first place.

There are many reasons that women do not work in India. Some that are suggested don’t really get to the root of this issue, or don’t represent it accurately for an Indian context. It’s important to separate these out from the ones that do.

Alice Evans asks (and later answers) the question:

Poverty can thwart progress towards gender equality. Poor girls usually quit school early, bear many children, become burdened with care-giving, then struggle to accumulate the capital, knowledge and networks to challenge dominant men.

So, does poverty explain India’s gender divergence?

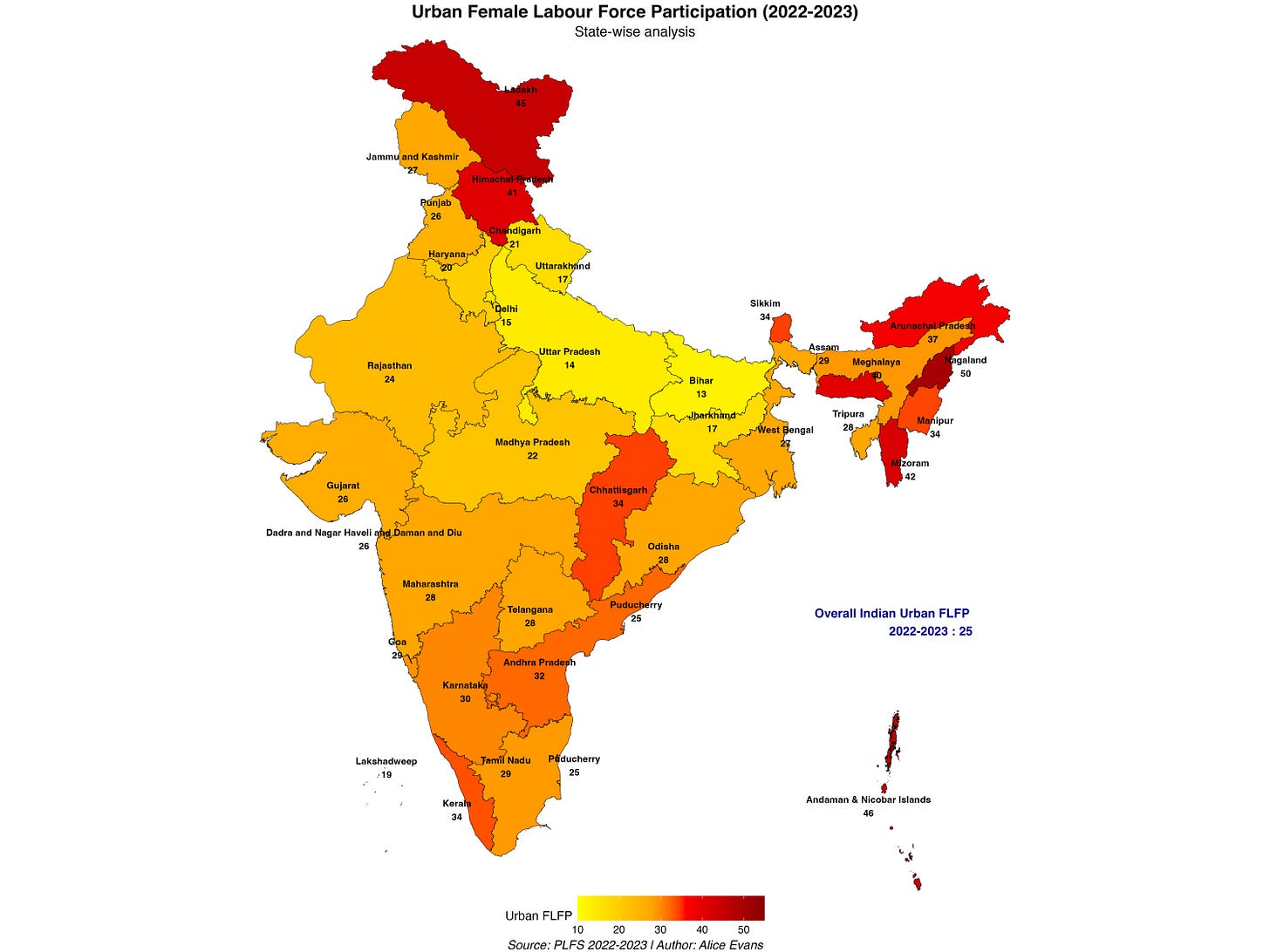

Not really. Consider this map of statewide FLFP in India:

Punjab and Haryana are both wealthy states and yet the FLFP there is lower than poorer states.

Another huge problem is the caste system, with more privileged caste families wanting to preserve a sense of purity by not having women work. But caste is an issue throughout this country, and yet Southern states have higher FLFP.

What about colonialism? Did the British screw us so badly that we haven’t been able to recover? Sure, they’ve caused a lot of our social problems, but that can’t explain the North-South divide since they affected the entire country. And they also can’t explain why we’re worse off than other countries under British rule.

Those reasons, while still contributing to this problem, aren’t useful when thinking about solutions, because they don’t present the full picture of why this problem exists in India.

A woman’s place is “in the kitchen, barefoot and pregnant” goes a common male joke. If you point out that this is misogynistic, they’ll say, “chill, it’s only a joke.” And yet, that is one of the most important reasons why India is so bad at FLFP: women end up having to spend a lot of time there.

Look at this graph. It shows the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to “unpaid care work,” meaning household chores like cooking, cleaning, and childcare. India’s ratio is 9.83. That means that for every hour of household work that a man does in an Indian household, women do ten hours of that work. No other country comes close!

Another big problem is cultural and religious beliefs. Because, in many of our cultures, women have been seen more as possessions than people, they were kept inside so as to protect them. This was more true in Northern India which was exposed to more invasions and raids. Furthermore, as India entered a period of Muslim rule, practices like purdah culture became prevalent throughout the northern regions of India, leading to more women being locked away at home, in a separate place just for them.

I should point out that although purdah and zenana were brought to India by Islamic cultures, we have now reached a point where a number of Islamic countries are better than us at FLFP. The problem really is of women being treated like possessions for men, to be kept locked away or stolen like gold. It isn’t an accident that the word “rape” used to be interchangeable with the word “theft” in the Age of Enlightenment. This is the thought process that still lingers today in issues like marital rape, where married women are seen as the possessions of the men that they are married to. If we see them as people, we’d let them decide their own fate, and protect them like anyone else.

Another thing that explains the difference in FLFP is the kind of farming that was historically practiced in that area. Areas which needed heavy cultivation using the plough automatically segregated into males working in the farms and women staying at home—because men have the upper body strength necessary for ploughing while the women don’t). Processes of wheat farming, more prevalent in Northern India, are like this. Comparatively, rice farming, while labour-intensive, is not strength-based, and therefore has historically been done by women.

In modern times, a lot of non-strength-based labour-intensive work is done in factories, and is a big driver of increased FLFP. Bangladesh is ahead of India because it employs a lot of women in its textile industry.

In India, the experience of the Foxconn factory in Tamil Nadu is instructive and promising. They employ a lot of women, and they did a bunch of things to make that happen. For example, there is a women’s hostel right next to the factory, with a 6 pm curfew in place—this makes it safer for the women and more importantly, makes their families more likely to allow them to work. And, the women don’t have to do as much household work and enjoy the company of other women in their hostels.

Alright, Alright, So How Do We Fix This?

There are some short-term fixes that provide some quick relief but don’t actually solve the problem.

Increase in wages: One of these is an increase in wages for women. This does make the work more enticing to the women, but research shows that if only the wages change and nothing else changes, then women stop working after some time.

UBI: UBI, cash transfers, MGNREGA, and other employment schemes work in the short run. However, women using these schemes often get work for which they have to travel long distances. The data shows that as they currently stand, these schemes do not provide a solution for women in the long term, and the women who take these jobs end up quitting them soon anyway.

UCC: Another solution you may have heard of is a Uniform Civil Code (UCC)—enforcing laws that combat the historical and cultural differences that have been created. But FLFP is low for Hindus as well as Muslims in India so it is unlikely that a UCC will fix anything.

Vocational/Skills Training: Similarly, vocational training that gives women marketable skills works in the short term, allowing women to do work than they wouldn’t normally do. But, again, research shows that these women are soon pressured by the men in their families to stop working.

So, what does the data support? What are the things that have shown to actually work in the long term?

Convenience: At the end of the day, women seem to be doing the work if getting to work is convenient for them. The big obstacle to women working in this country specifically seems to be the unpaid care work they are being forced to do in households. This leads us to more effective, more permanent fixes to this problem.

Childcare: Free childcare plays a big role. If taking care of children becomes easier, women have more time to work. Claudia Goldin won a Nobel Prize for pointing out that if women’s domestic lives were as easy as men’s, they’d be working a lot more. In a similar vein, if women are given concessions for the slavery the patriarchy has put them under, like flexible work hours, and the ability to work from home sometimes, they are far more likely to work.

Labour-intensive work: The government should invest in having more labour intensive factories that specifically employ women. In general, it could do more to provide work specifically to women all over the country.

Safety: Safety is another huge issue. The ways by which women get to work must get safer. There are some initiatives that have been focusing entirely on this issue. For example, check out the Why Loiter? Campaign, which is attempting to reclaim the streets and public spaces for women.

Data has shown that sexual harassment training, and more importantly, robust and reliable processes through which women can address grievances regarding sexual harassment, are huge factors in bringing women to the workplace.

Role Models: Another big factor is visible role models. Research shows that female leadership influences adolescent girls’ career aspirations and educational attainment. For this to happen, there needs to be more researvations for women in leadership positions, and more awareness campaigns around this. Awareness campaigns do work, but their effectiveness depends a lot on the intensity and approach. “Light-touch” awareness campaigns—which are easy to do with minimal effort (like creating awareness videos)—don’t move the needle much. They need to be combined with visibility for actual role models in real-life.

Men: But more than anything else, men have to be held accountable. We must start helping out around the house more. We have to make the streets safer. We have to call out the casually misogynistic jokes. We have to recognize how much we have messed things up for the women of this country, and start undoing that damage at a personal level. We don’t talk about men’s responsibility in this nearly enough. It starts at home, and it starts with us.

Summary

India is especially bad in getting women to work, for cultural, religious, communal, and safety reasons. And this is holding back our economy, equality, and many other things. How do we fix it: make it easier for women to work. Men: do more household work: our women to men household work ratio is at 10, the world in the world. Let’s at least get to 5x, like repressive Islamic countries. Employers: make it easier for women employees to get childcare. Make it easier for them to have flexibility. And celebrate the role-models. This is why, for example, the “woke” practice of insisting that panels have women members is important.

Further Reading and References

There is a lot of fascinating literature on this topic and I have left out so much (for example, in North India, women’s participation in the labour force reduces when the wealth of the community increases). I would recommend that you read at least the first four of these (which themselves link to dozens of other papers).

Alice Evans interview in Scroll.in, India’s Big Feminist Demand Should be Labour-Intensive Growth: https://scroll.in/article/984100/interview-alice-evans-on-why-india-s-big-feminist-demand-should-be-labour-intensive-growth

Alice Evans, Why do Women in South India have more freedom than North: https://scroll.in/article/975151/why-do-women-in-south-india-have-more-freedom-than-their-northern-sisters

Hindustan Times article on Claudia Goldin’s work and women in the workforce in India: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/an-acknowledgement-of-women-s-work-in-economics-hits-misses-and-a-long-road-ahead-101696875659892.html

Shruti Rajagopalan and Alice Evans discuss the status of women in India, the need for structural transformation: https://www.mercatus.org/ideasofindia/alice-evans-great-gender-divergence

Vocational training programs work only temporarily: https://www.theigc.org/blogs/vocational-training-programs-india-are-leaving-women-behind-neednt-be-case

Female Leadership Raises Aspirations and Educational Attainment for Girls: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3394179/

Providing childcare helps Indian women work: https://sociologyofdevelopment.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/leila-gautham-no-2-2023.pdf

Gender Parity could boost India's GDP by 27% (IMF): https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/gender-parity-can-boost-indias-gdp-by-27-wef-co-chairs/articleshow/62589586.cms

McKinsey on Gender Parity in India and its impact: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/indicators/bridging-gender-gap-may-add-rs-46-lakh-crore-to-indias-gdp-in-2025-mckinsey/articleshow/49628430.cms

Foxconn in India: https://econforeverybody.com/2023/11/29/markets-are-complicated-foxconn-in-tamil-nadu-edition/ and https://restofworld.org/2023/foxconn-india-iphone-factory/

What can Architecture tell us about Gender: https://www.ggd.world/p/can-architecture-reveal-the-spread

UNDP Women at Work Report: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/in/Women-at-Work-Report.pdf

FLFPR India vs comparable countries: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.ACTI.FE.ZS?locations=IN-BD-CN-ID-LK-PH

OurWorldInData, Female Labour Force Participation around the world: https://ourworldindata.org/female-labor-supply

About the Writer

Thanks to Arsh Kabra for writing this article based on my notes because I’ve not been getting the time to do that myself. Arsh, who is my son, is a freelance writer who lives and breathes stories. Whether it’s scripting for YouTube channels, running epic Dungeons & Dragons adventures for young minds at Flourish School, or bringing plays to life on stage, he’s always finding new ways to spark imagination--both for himself and anyone else he can get a hold of.

India has low Female Labor Participation Rate (FLPR), but I don't think it should be compared to Islamic African nations.

Most African nations employ about 70% of their workforce in agriculture. And in rural communities with high agricultural dominance, women have higher labor participation.